HMS ABDIEL – HER ROLE AT JUTLAND

HMS Abdiel, a newly built fast minelayer, joined the Grand Fleet in early 1916.

Soon after the main battle commenced, Abdiel took up her station close to Jellicoe’s flagship. the Iron Duke. The ship, with a full load of mines, was effectively a floating bomb which could easily have been detonated by a single enemy shell whilst their own 4inch guns did not have the range to participate in the fleet action. However, the Abdiel remained unscathed and the main action was broken off at about 21:00 when the German fleet began to retire towards its base at Wilhelmshaven.

At about 21:30, Commander Curtis was ordered to proceed at high speed towards the German coast to extend the minefield he had previously laid off the Horn Reef (on May 3rd and 4th) and in the path of the retiring German fleet. To achieve this, he had to take HMS Abdiel through the ongoing but somewhat scrappy battle between the opposing squadrons and get behind the German fleet. Had Abdiel stumbled across even a minor German warship the results would probably have been fatal but Commander Curtis succeeded

in his task and laid the mines off the Horn Reefs at between shortly after midnight in the morning of 1 June. Abdiel then returned to her base at Rosyth, again passing through the High Seas Fleet. Later, at about 06:30, the German battleship, SMS Ostfriesland on its way back to Wilhelmshaven, stuck and was damaged by one of her mines. Admiral Jellicoe, in his formal report, wrote the following:

“Abdiel, ably commanded by Commander Berwick Curtis, carried out her duties with the success which has always characterised her work.”

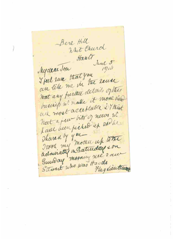

Commander Curtis own account, written as a letter. was very understated :

“Abdiel had no active part as far as fighting was concerned in the Battle of Jutland, and one cannot make a good yarn out of it. Up to the time of meeting the Germans we were working with the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron, stationed 5 miles ahead of the Battle Fleet and steaming in line abreast, ships a mile apart. When the fleets sighted each other and the deployment signal was made, the 4th LCS went off to their station ahead of the line but Abdiel remained where she was until the fleet had nearly completed deploying, by which time the “overs ” from the Germans, strafing two of our four-funnelled cruisers about half a mile south-west of us and the three battle

cruisers led by Invincible about half a mile to the south-east of us, came buzzing about and bursting round us. I, therefore, legged it round the head of our battle line, which had finished deploying, and managed to get through four lines of destroyers taking up their position ahead of the fleet, and finally got to my battle position half a mile or so on the disengaged beam of the Iron Duke. Here we remained until dusk. At about 9.30 pm I got orders to proceed to a position south of Vyl Lightship and lay a line of mines. We therefore went off at 32 knots, passing on our way several ships in the distance, and also a flotilla of sorts which were making a great deal of smoke, but as we were not making any smoke ourselves, we presumably were not seen. We reached our position about 1 a.m., and laid the mines, then returned to Rosyth for another load, passing south of the big North Sea mine area. Abdiel was not hit during the battle, and did not have any action with any German destroyer or big ships, but we got a very good view of the whole show between 6 and 8 p.m. We had 80 ordinary mines and 10 Leon mines on board, all primed, so perhaps it is just as well that we weren’t hit. The ship did exactly what she was intended to do, justified her existence, and that’s all there is to it.”

HMS Abdiel’s flag at Lawford.

The Battle Ensign flown by the minelayer HMS Abdiel at the Battle of Jutland (which normally would have flown from the foremast or mainmast) was left at St Mary’s Church, Lawford by her captain, Commander Berwick Curtis. Originally it was on public display but it seems to have been removed and stored in the Church away from public display in recent years.

(Kindly submitted by David MacDonald and based on his account).

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Abdiel community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2963

HMS ACASTA

HMS Acasta was originally going to be called HMS King. One account of her action at Jutland is below :

« Acasta was very badly mauled in her encounter with German light cruisers and was finally so damaged that she lay drifting close to the course of the German battleships. She had a list to starboard, two large holes just abaft the third funnel, one large hold forward on the port side, and sat very low in the water, her guns and torpedo tubes still trained aneam and they had been during the action. As the fleet flagship, HMS Iron Duke, came rushing by, firing her guns and leading her division, the men of the plucky little destroyer rushed out, forming a lime from the forecastle head to right aft and gave their Commander-in-Chief three heary cheers. Acasta was afterwards take in tow by Nonsuch and brought safe to port (Aberdeen).»

She had suffered some heavy casulaties :

· Engineer Lieutenant James Forrest

· Chief Petty Officer Stoker Richard Massey who is buried at Anns Hill, Gosport (from whence many of my family came)

· Chief Stoker George Howe who lies buried in Milton Cemetery, so either he died of wounds or his body was recovered.

· Engine Room Artificer James Bailey, buried Horsham

· Herbert James Bailey who was taken to Horesham for hospitalisation by train

I think John Barron, her thirty three year old commander was unhurt.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Acasta community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2561

HMS AGINCOURT

A YOUNG LIEUTENANT’S REPORT ON JUTLAND

Lt. Horatio Westmacott, HMS Agincourt

I write this now but don’t know when I shall be allowed to send it off on account of the Censor. As I think I told you before the Navy has been sending occasional parties out to the trenches to get some idea of the fighting in France and bring back stories to relieve the monotony of their shipmates. Well, the Army retaliated by sending some Officers up to the Grand Fleet to see what we were up to. There were to arrive by 8.o’c in the evening and one, a Captain in the R.E., called Webb was to be accommodated in the Agincourt. That afternoon we were ordered to raise steam with all despatch and an hour or two after the soldiers were aboard we got under weigh. The rumour went around that the Huns were out but they have been out pottering about in their own waters so often before, and we have always hurried out to meet them, only to find that before we could get near they would slip back, so we took little account of the rumour expecting that our trip would fizzle out in the same way that it has one hundred and one times before. It was the real thing this time and what we had been waiting very nearly two years for the soldierman who had come to pay us a visit of days sees almost at once. He must think ours a giddy life. Well to get on with the story. The night before the action I had the middle watch, that is 12 to 4. The next afternoon we exercised action stations for about an hour my station being the foretop, namely the foremast from where I control the 6” guns of which we have ten aside. By control I mean that I get orders up a voice pipe from the Captain in the conning tower to open fire on such and such ship and I do the rest, viz, give them the bearing of the enemy, range, deflection, etc, and keep altering the range so as to keep trying to hit the enemy. After finishing our exercise we had lunch and I got into my chair for a well earned snooze, having been up half the night. The Fleet all this time was steering in the direction where the Admiral had news by wireless of the enemy, and we were still in a state of apathy, expecting the whole thing to come to nothing. However about 3 o’c in the afternoon we were wakened by a signal from the Fleet Flagship to “prepare in every respect for instant action” which entailed a busy hour’s work for us doing the thousand and one little things that had to be done, different of course in every ship. My job was to see a number of the men’s hammocks stowed down below out of the way and then to see a lot of tubs and fire buckets in different parts of the ship filled in case a fire system should get shot away in any part. By the time I had done that it was after 4 o’c and it was my first dog watch, viz, 4 to 6 I had to rip up on the bridge having had no tea. During the first dog we kept hearing reports by wireless, that the battle cruisers and our faster battle ships were engaging the enemy. About a quarter past five we could hear firing but the weather was very hazy and we could not see them, visibility about 7 miles. At about 10 to 6 we saw the flashes of guns on our stbd bow, we had gone into action about 10 minutes previously. The Captain had had it piped round the ship about 10 minutes before that the battlecruisers were engaging the enemy which brought forth a rousing cheer and all rushed off to their stations full of excitement.

As officer of the watch I had of course been in charge of the ship up to that moment so I turned over to the Captain and went up the foremast to my station. On arrival there I got the report that both my batteries were ready for opening fire, which I passed on to the Gunnery Dept and then proceeded to wait my chances. The flashes we had seen were our own battlecruisers firing on the enemy. They crossed ahead of us aamd presently through the smoke we made out the enemy and opened fire on them with our 12” guns, of which we have 14. They are controlled by the Gunnery Commander from a position on the foremast just above mine. The reason we are up there of course that to a certain extent it puts us above our own smoke and also one can see further. The higher you are the better you are able to spot the fall of shot. With a low visibility one could see flashes everywhere but it was difficult to make out ships , however we saw our 12” were hitting all right first firing at a cruiser and later at the battleships as they came in sight My old ship the ‘Defence’ passing close to us to take up her station was being fired at by enemy ships that were out of sight from us. I saw three salvos of shots that were falling all around her and the fourth got her. It must have been a hit in some magazine for there was a tremendous explosion before she sank. Later we passed a ship, bottom up. I should judge from the size and colour that it was a German light cruiser, but I have no means of telling at present. We also passed one of our Destroyers with all hands on the upper deck flying the signal that they were in imminent danger of sinking. Great columns of water springing up all around us caused by the big shells firing at us, they sent up a column higher than the mast of the ship, the ship next ahead of us was straddled, viz 3 shots short and 2 over, luckily not hit by a salvo and we saw the water streaming off her as if she had suddenly plunged into a heavy sea . We were hit by lots of small splinters from the big shells bursting but no direct hit and very little damage done. The decks a bit scored in places and most of the boats had a hole of two in them. My chance didn’t come at first but later after about half an hour the enemy developed a destroyer attack and out of the haze about 60 degrees on our starboard bow a lot of destoyers came racing towards us. I opened fire at about 9000 yards and managed to cripple 0ne, for we counted five direct hits and the rest then turned away without getting in their attack, leaving one disabled behind. I did not see it sink but our destroyers must have finished it off alright as it could not steam. We saw the tracks of torpedo’s fired at us at various times and three times had to alter course to avoid them, two passing ahead and one astern, all pretty close shaves for us we also saw one torpedo break surface about 50 yds abeam of us having run its full course and just not reached us, so we were quite in luck’s way. Our flagship, the Marlborough, was hit by a torpedo but managed to stay on till the ed of the action. She had a list of about 5 degrees but it reduced her speed very little. During the night the admiral transferred his flag to another ship and the Marlborough made off to the nearest harbour where she arrived safely. We lost the enemy in the haze and dark that was coming on. During the night we saw lots of flashes from guns along way from us, Destroyer attack certainly , but on whom I don’t know. I got no sleep that night, being in the foretop all the time constantly on the lookout. About 10:30pm I was relieved for about half an hour to get my food, my first since lunch at noon and to put on warmer clothes for the night. Some time at about 16:30 in the morning we sited a ZEP, which we had a bang at but I fear made no impression. There is I think nothing more to tell you. I only hope that next time we come up with them it will be in the morning and not the evening, there will probably then be more to write about. I am tremendously in luck being stationed in the foretop for I could see all there was to be seen and one can’t conceive a grander spectacle than a Naval Battle.

Written June 3rd, 1916, HMS Agincourt.

(Kindly submitted by Adrian Wildish. Lt. (later Captain) Horatio Westmacott was Adrian’s maternal grandfather. Horatio was from Probus in Cornwall, where his father was the local Parish Priest. His tomb is there along with Horatio’s brother who was killed during the war and whose name is on the local War Memorial. Horatio developed Multiple Scorosis and died in the late 1950’s in Torquay Devon.

A lucky Posting to Agincout

Aged thirteen, Herbert (Bertie) Acheson Forster went to Dartmouth as a naval cadet As war broke out, joined the crew of HMS Invincible His posting had changed from the Victoria & Albert to Invincible so that he could accompany other officers of the Royal Yacht to the new dreadnought, purchased by the Turkish Navy, but now commandeered as HMS Agincourt. This saved his life as, tragically, Invincible sank with all hands. In 1937 he retired as Rear Admiral Forster MVO, RN.

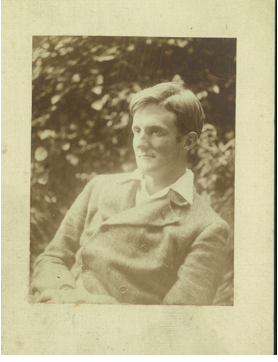

Herbert (Bertie) Acheson Forster (Courtesy of Michael Nurton)

HMS Agincourt’s origins

HMS Agincourt was originally been built for the Turkish navy and would have ben known as known as the Sultan Osman. As the situation in Europe heated up Churchill was getting ready to sieze the ship and keep her for the British Royal Navy. On July 31st (after Russia had mobilized) he told Armstrong Vickers, her builders, of his intentions. At 14:30 that afternoon the Turks paid a large installment (£800,000) into the Vicker’s account. Immediately Churchill ordered her siezed, bot telling the Turks. British sailors boarded her and took her over within minutes.

It is felt that this action heavily contributed to Turkey entering the war on the German’s side. With all its consequences at Gallipoli. It’s thought that Enver Pasha had offered the Germans the ship knowing that it was going to be siezed which then led them into a more aggressive role of rupport.

The ship became known as the « Gin Palace » Inside,when she’d been siezed, she had already been outfitted with fine Turkish carpets.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Agincourt community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2938

HMS AMBUSCADE.

Help us raise money for heroes.

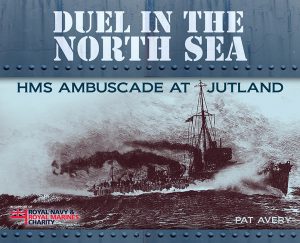

Pat Avery, grandson of the Telegraphist who served in the torpedo boat destroyer HMS Ambuscade during the Battle of Jutland 100 years ago, has published a book, written to raise money for the Royal Navy’s principal charity.

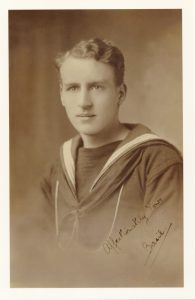

Ldg Tel Basil Phillips J10426 HMS Ambuscade

The book, Duel in the North Sea: HMS Ambuscade at Jutland (Sea Funnel, ISBN 978-0-95479-5313 £10), has been released to commemorate the centenary of the battle, and documents what was the most intensely contested and significant naval engagement of the First World War. All proceeds from the sale of the book goes directly to the Royal Navy & Royal Marines Charity

As a direct descendant of one of the sailors involved in the Battle of Jutland, Pat, together with other family members, was invited by the Government to the special Centenary commemorative service held in St.Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Orkney on 31st May, an event attended by HRH The Princess Royal, The President of the Federal Republic of Germany, and Prime Minister at the time, David Cameron.

Pat said afterwards “It was a tremendous honour and privilege to be present on such a momentous occasion. Not only to remember my grandfather, but all the officers and men on both sides, particularly those who made the supreme sacrifice.”

Another highlight for Pat in connection with the book was an appearance on the BBC TV programme Songs of Praise, which was first screened on BBC1 on 29th May. Filming took place in Belfast aboard HMS Caroline, the sole surviving ship from the Battle of Jutland.

Pat Avery on HMS Caroline on May 29th 2016 where Songs of Praise was filmed.

Admiral Sir Philip Jones, First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff, said: “This book is a personal contribution from a naval family, but it also reflects our national story. Britain was dependent on the sea for security and prosperity in 1916, just as we are today. The Battle of Jutland ensured the Royal Navy retained its supremacy. Famous for being a clash between battleships, this book rightly remembers the men who served in the numerous smaller, but no less gallant, ships of the Grand Fleet and the vital role they played in the battle.”

Lauren Wileman, representing the charity, said: “The book gives an excellent personal insight into the battle. We are very grateful to be receiving 100 per cent of the profits from the sale of copies of the book. It is an extremely generous gesture from Pat in support of the Charity. Donations generated from the book will go toward helping naval veterans of all ages, as well as those serving today and their families.”

(Courtesy of Pat Avery)

To order, please visit the publisher’s website at: www.seafunnel.co.uk

HMS ARDENT

Arthur Harold Cragg was a Petty Officer Stoker on board HMS Ardent. He had only just been married while on his final shore leave before the battle. His diaries have been digitized by his great great nephew and I hope we can share some of them soon.

(Courtesy of Neil Armstrong)

HMAS AUSTRALIA – THE SHIP THAT SHOULD HAVE BEEN AT JUTLAND

Just weeks before Jutland, HMAS Australia, suffered a cruel fate at the hands of her sister ship, New Zealand, in a ramming incident in bad weather conditions. It caused considerable ill-will between the ships’ companies.

HMAS Australia was launched in 1911 and commissioned as the flagship of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) in 1913. Her immediate role in the naval war was hunting for Admiral Graf Spee’s German East Asia Squadron. She was diverted to New Guinea and Samoa and, as a consequence, could not take part in the destruction of the German force. And, because she was out of action at Jutland, is reputed to have only fired her guns on two occasions. Once in January 1915, against a German merchant vessel and in December 1917 at a suspected German submarine.

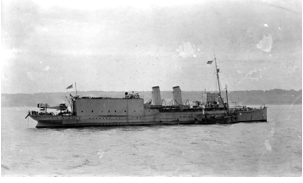

HMS Australia before Jutland

HMS BARHAM

HMS Barham was one of five fast battleships of the Queen Elizabeth class.

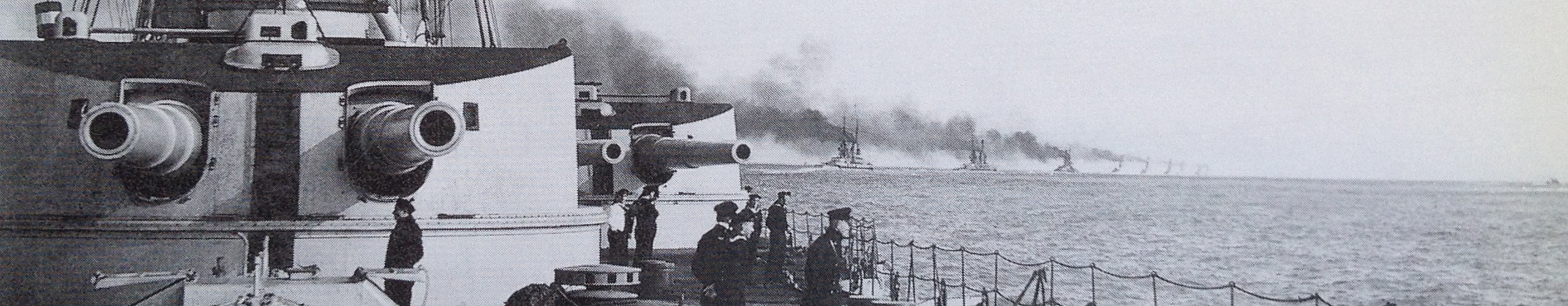

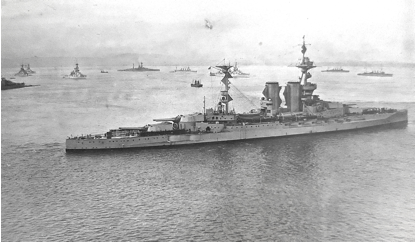

HMS Barham leading the 5th Battle Squadron in heav weather (private collection)

HMS Barham at anchor in Scapa Flow (private collection)

She was commissioned on August 1915, and at Jutland, as Rear Admiral Sir Hugh Evan-Thomas’ flagship received six hits. With one of her sister ships, HMS Valiant, the two made 23-24 hits on evenmy ships during the battle, mostly in the so-called “Run to the North”.

Rear-Admiral Sir Hugh Evan-Thomas (private collection) with his beloved “Jutland Jack”

Her end in the Mediterranean in the Second World War was as a result of a torpedo attack. The full explosion was horrific and captured on film from rolling over to catastrphic explosion

Imperial War Museum HMS Barham community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2315

Pathé Newreel footage of HMS Barham explosion :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YdrISbwy_zI

HMS BELLEROPHON

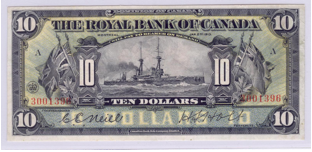

The battleship known as The Billy Ruffian was used on Canadian currency

Bellerophon was at Jutland as part of Admiral Doveton Sturdee’s 4th Battle Division. She left the battle undamaged and had fired around 62 heavy shells.

When Bellerophon later crossed the area where Rear Admiral Horace Hood had been killed with almost his entire ship’s company, a 19 year old “snottie” (a term, I won’t say of endearment, used for midshipmen in the Royal Navy), commented on the terrible carnage.

“During the lull we came out of the turrets to get some fresh air and there, floating around us, was a whole mass of bodies and débris – some of our sailors were cheering because they thought they were Germans, but unfortunately they were from the Invincible. It was a terrible experience and my first experience of death.”

HMS Bellerophon was on the Royal Bank of Canada’s 1913 $10 note.

Imperial War Museum HMS Bellerophon community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2799

HMS BENBOW

The story of two brothers who fought in the biggest naval battle since Trafalgar

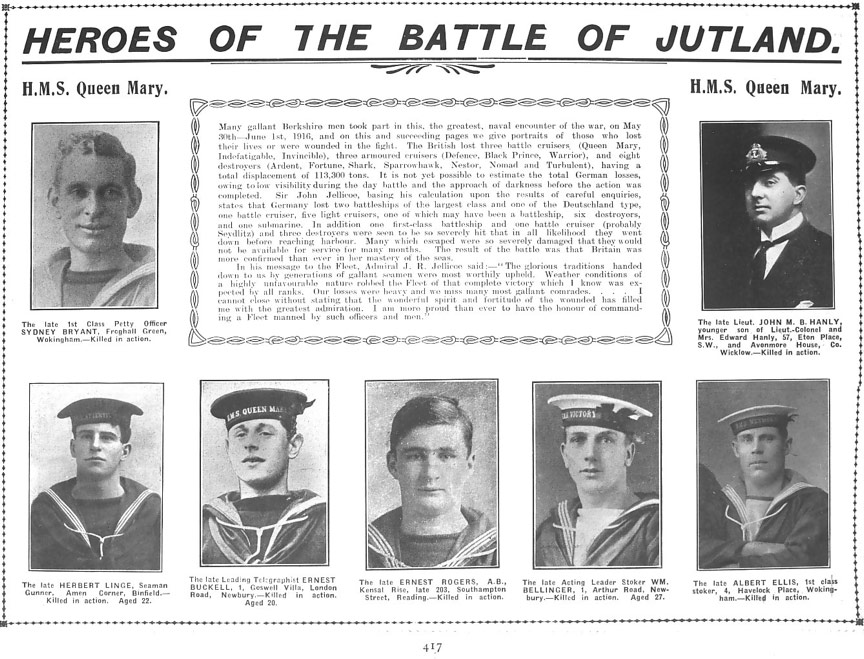

During the fourteen or hours of action at Jutland, 8,500 men were killed on both sides. One was Alexander Kasterine’s sixteen year old great uncle Archibald, then servicing as a midshipman on new battle-cruiser, HMS Queen Mary (she’d only been in service three years). His eighteen year old brother Robert “Bertie” Dickson, his grandfather, was also in the battle and survived unscathed.

Bertie witnessed the main action through the periscope in his gun turret on the dreadnought HMS Benbow. In a series of letters between Bertie and his parents, kept in the archive of the National Library of Scotland, Alex learned of the horror and spectacle of battle, a young man’s pride at victory over the enemy, the parent’s and brother’s grief of losing the youngest member of the family, and a mother’s anger at the incompetence of a British Admiral.

Archibald and Bertie grew up in a comfortable and happy household in Edinburgh. Their father, William, was the Director of the National Library of Scotland, their mother, Kathleen, the daughter of General Murdoch Smith a Royal Engineer who had spent much of his life as diplomat in Iran overseeing the construction of railways and spying in the Great Game against Russia.

Family albums show photographs of the two boys with adoring parents and enjoying summer holidays fishing, tennis and beachcoming across Scotland. However, the boys were destined for early adulthood and at the ages of 12 were sent to Dartmouth Naval College to train as midshipmen.

Bertie (shown on the left) and Archibald Dickson together for the last day before they both returned to their ship before the Battle of Jutland, May 1916

In August 1914, their parents made the long journey to visit the boys at naval college. As they sat picnicking and watching a college cricket match, an officer ran onto the pitch announcing that Britain had declared war with Germany. The boys bid farewell to their parents and ran from the pitch to join their ships. They did not see Bertie for another two years, not till the eve of the Battle of Jutland.

Death in war is a lottery. Archie was sent to the battle-cruiser HMS Queen Mary, known as the “pride of the navy”. His older brother Bertie joined HMS Benbow a dreadnought battleship.

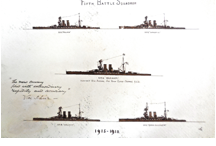

Bertie’s first sight of the battle was at the start of the second and heaviest engagement, just after 18:00, crouched inside one of Benbow’s gun turrets. Looking through his periscope he drew sketches of the battle and in a letter to his father, describes how saw the enemy coming into view at the same time as Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty’s Battle-cruiser Fleet. Bertie noted that he could not see his brother’s battle-cruiser, Queen Mary, that formed part of Beatty’s Fleet.

“The Battle-Cruisers were being straddled continuously, great columns of water rising all round them. We waited anxiously for a glimpse of the Queen Mary and Indefatigable, but they never came. They had gone before ever we arrived”.

Unknown to Bertie, an hour earlier, his brother Archie had been killed along with 1,285 other men when the Queen Mary was destroyed in the first phase of the battle. Another cruiser the Indefatigable was also destroyed in the same action with the German Scouting Group with the loss of 1,000 men.

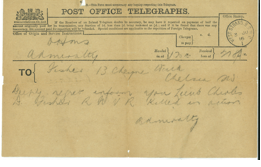

Two days after the battle, Alex’s great grandparents received a telegram at their home in Gloucester Place, Edinburgh with the words “DEEPLY REGRET INFORM YOU MIDSHIPMAN ARCHIBALD W DICKSON KILLED IN ACTION + ADMIRALTY”.

Alex’s great grandmother, Kathleen, wrote to her only surviving son Bertie of her grief.

“My dearest and only boy, We can’t tell each other in writing what we are feeling today – my world was divided into three parts, or a third has crumbled away. You will, I hope, be some boy’s Father some day, but you can never be his Mother, so you can never know what I am feeling now.

I am telling the simple truth when I say, that all mothers and sons are not what we were to each other. He had needed me so much always, and I was perhaps too proud of the big handsome man my delicate kiddie was growing into. Thank God you missed being in the Queen Mary ”.

Archie and Bertie’s father, William Dickson, found some solace in what many considered at the time to be a victory for the Royal Navy, but the pain was acute for him too.

“It seems impossible to believe that we shall never see Archie again and that he, and his friends who used to come here, and that splendid ship of which they were all so proud, are at the bottom of the sea.

It is good to know from your letter and from all we hear elsewhere, that the results of the action have been so much better than appeared from the first news, and that all their sacrifices have not been in vain.

He quotes the reassuring words of a Commander Sands who had written to him to say

“you have at least the proud satisfaction of knowing that he fell doing his duty in a greater and perhaps more decisive action Trafalgar”

But that won’t bring Archie back. It is a terrible blow to Mum, but she is bearing it very bravely”.

Bertie wrote to his father, once it was confirmed that his brother was dead.

“The hardest truth is better than that awful uncertainty. I wonder if you saw him that last Sunday? I can picture it yet. I can’t realize coming home again and not finding Archie with you or at Rosyth. All our two lives we’ve been in a family of four and its heart breaking to think of all those happy holidays we’ve had and the home life that can never be the same again…In all the two years abroad last commission I never wanted to be home with you like I do now, but in all our troubles we must not think of our selves”.

By 4th June, Kathleen grief had turned to anger, specifically towards Vice Admiral Beatty.

“There is no end of a flowing account of the battle in the evening paper – it must be very badly informed, for if, as would appear from it, Beatty engaged the German Grand Fleet with his five Cruisers, for no better reason than to demonstrate British pluck, he would deserve to be shot.

Immediately after the battle, Archie’s grieving mother had asked his surviving son to write to the survivors to find out more about the circumstances of Archie’s death. Two of the 20 survivors wrote to Bertie, describing the likely last moments for Archie. Midshipman Jocelyn Storey was in “X” turret with Archie.

“At about 5.20 a heavy shell hit our turret and put the right gun out of action but killed nobody. Three minutes later an awful explosion took place which smashed up our turret completely. The left gun broke in half and fell into the working chamber and the right one came right back. A cordite fire got going and a lot of the fittings broke loose and killed a lot of people. Those of us who were left got open the cabinet door and got into the S. cabinet. I did not see any sign of your brother and don’t know what happened to him…whether he was killed by the explosion or the fumes I can’t say.

Storey was able to get out of the turret and sat on the side of the listing ship,

“where the after magazine went up and blew us into the water. When I came up the ship was gone and there were very few swimming in the water. I saw your brother nowhere….I think that is all I can tell you as I did not see him after the action started properly but just before he seemed quite happy not in the smallest degree”.

A month after the battle, Bertie wrote to his mother saying how he thought Archie met his end.

“I think myself that Archie was killed in the cabinet, knowing the construction of the 13.5” turret. I know that he was in the right hand corner of the cabinet, because he showed me his action station when I was onboard. Story say “the right gun came right back”, so one can well imagine the end.

How I wish someone had been saved who had seen him in those last moments before the ship sank, and who had spoken to him. But nobody need tell you that his last thoughts were of you and of home, and to no one who has fallen in this war have those thoughts been happier, more loving, or brought greater comfort”.

The second correspondent and surviving shipmate, Petty Officer Ernest Francis described to Bertie, the turret’s early success in the battle but also its last moments.

“We fires off 30 rounds and observes one of the German ships falling out of the line “First blood to Queen Mary”. Then came the big explosion, which shook us a bit … Immediately after that come what I term the big smash, and I was dangling in the air on a bowline, which saved me from being thrown down on to the floor of the turret. The turret was destroyed and the Lt gave the order to clear the turret.

Francis described what historians agree was the main cause of the Queen Mary and Indefatigable’s destruction.

“To finish my account, I will say that I believe the cause of the ship being blown up was a shell striking “B” turret working chamber igniting the shells stowed there in the ready racks, and the flash must have passed down into the magazine, and that was the finish”.

In one of the first engagements of the war, the Battle of Dogger Bank, a German ship, the Seydlitz, had nearly suffered the same catastrophic magazine explosion because its magazine was not protected from flash. The Germans immediately introduced modifications to their flash control ensure it did not happen again. The British navy did not make such changes.

The second reason for the Queen Mary and Indefatigable’s destruction was a tactical error by the British commander Beatty. Whilst subject to debate and controversy after the battle for several decades, modern historians agree that Beatty had made a fatal error in the battle.

Through poor communication he allowed his Queen Elizabeth class ships in the 5th Battle Squadron to become separated so that in the early stages of the action, these heavily armoured super-dreadnoughts were trailing behind, increasing the likelihood of British losses.

Beatty was also criticized for not firing at the German ships earlier enough and taking advantage of his ships greater range. At Beatty’s flagship, HMS Lion, was hit and fell temporarily out of line, the Derfflinger’s gunnery officer directed fire at the Queen Mary which was already being targeted by Seydlitz. After hits to its turrets from the two German ships, the ship listed to its port and a series of explosion destroyed the bow and stern. As men escaped the turrets and began to jump into the water, the ship exploded.

From the bridge of Lion, Beatty observed the 800 feet high explosion of fiery smoke that obliterated the Queen Mary. His Captain recalled that Beatty turned and remarked:

“There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today”.

Beatty and his remaining Battle-cruisers followed by the lagging 5th Battle squadron headed north and draw the pursuing German ships into the jaws of Admiral Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet who were steaming south toward Beatty. Communications from Beatty were again at fault as he gave incorrect information on his position so that as Alex’s grandfather on one of Jellicoe’s fleet’s ships observed

“…we sighted him half an hour before we expected to, and before the armoured cruisers had got into position”.

Despite this, Jellicoe quickly manoeuvred his fleet to port creating the first of two “crossed Ts” that meant the approaching German fleet was subjected to heavily concentrated British fire.

Beattie emerged from the gloom at great speed in what must have been a dramatic sight for the eighteen year old on Benbow.

“Led by the Lion, they (the British cruisers) suddenly burst through the mist on the starboard bow. Lion, Princess Royal, Tiger and New Zealand; they tore past us at full speed, their great funnels and superstructures silhouetted against the sheets of flare and thick cordite smoke as they fired salvo after salvo at the enemy whose flashes could now be seen in the distance between the ships. It was a wonderful sight. The Lion had been hit and was smoking forward. (Admiral) Beatty passed across the bows of the Battle Fleet and went right ahead of everybody….”

By 18:30 the two main fleets were heavily engaged. A few minutes later another line of British ships passed between the two fleets, as described by Bertie.

“(Admiral) Bobbie Arbuthnot was trapped on the weather side of the Fleet, and with his speed, was unable to follow the Battle Cruisers to the Van. He had no choice but to lead his squadron down our whole engaged side, between us and the enemy … He made a splendid fight of it, firing at a tremendous rate the whole time, but getting terribly mauled. At 6.20, just as he got on our starboard quarter, his flagship, the Defence, was blown to pieces by the most appalling explosion. She was turning, and a salvo hit her. A great flame shot up, followed by a pillar smoke and steam.

“All ships of both Fleets were firing now…The action had now become pretty fierce although the enemy’s firing from the time our Battle Fleet arrived became very poor indeed, in fact at times we wondered who they were shooting at. The fight developed on a roughly semi-circular course, with many alterations of course and speed. We were engaging both battleships and battle cruisers at a maximum range of about 16,000 yards. Four Kaiser class battleships were now plainly visible. Shortly after 630 a ship of this class was seen to haul out of the line badly on fire, turn over and sink. One enemy light cruiser with three funnels, although she may originally had four, drifted down disabled between the lines, burning fiercely”

As dusk fell at 18:46, the German fleet “altered course to starboard and disappeared”. Fearing torpedo attack and mines, Jellicoe did not pursue, a decision for which he was criticized by some for missing an opportunity to maul the enemy but praised by others as the enemy returned to its port where it stayed for the duration of the war. Pursuing the enemy was not necessary to achieve the same result and two years previously the Admiralty had agreed that the British fleet would not pursue the Germans in such circumstances.

However, fierce firefights continued during the night.

“An enemy’s battle cruiser now appeared on our starboard quarter. Some observers think it was a battleship of the Koenig class, but most agree now that it was the Lützow. Ranging commenced and at 19:17 we opened fire at 13,000 yds. We gave her five salvos of 13.5 lyddite of which the third took effect. A great flame shot up from her quarter deck, setting the after part of the ship on fire and she disappeared into the mist blazing”.

Bertie’s letter describes his dreadnought dodging torpedoes and thus gives an idea of why Jellicoe felt pursuing the German fleet would leave his fleet vulnerable to a destroyer attack.

“Endless forming and disposing began after this and for nearly an hour we did innumerable 9 pendant turns, increasing speed to 20 knots. At 8.30 the third and last destroyer attack was made by the enemy bearing NNW and this ship was very nearly sunk. We had to put the helm hard a port and stop the starboard engine to avoid a torpedo which passed immediately ahead. We replied with one rippling salvo of 6” which completely repelled them. These were our last shots. At 9.00pm we ceased fire, having been engaged intermittently for 2.5 hours, and the general action was broken off in the darkness and the mist which now came down thick and cold”.

The following day, Bertie’s ship searched for survivors.

“We passed through miles of oil and wreckage, and many dead bodies in lifebelts, but no sign of the enemy, except his submarines which were reported at 9,30 and which kept us on the jump for a little….

Later in the afternoon, the weather worsened and burials at sea took place

“The barometer had been low all day, but now it fell rapidly, and an icy wind accompanied by choppy seas came down on the Fleet. At 7pm all ensigns were half-masted while the bodies of men who fell in action in Barham and Malaya were committed to the deep. The seas were coming on boards some of the ships and spray was sweeping along the decks. Surely no men ever had a wilder burial”.

A week later, back in their base in Scapa Flow, a more formal burial took place

“Each ship sent 60 men and 4 officers. We formed up in a great long line inland from the sea. Then the Commander in chief and all the Flag Officers and their staffs passed silently up the line and headed by the massed bands of the Iron Duke, Benbow and Colossus, we marched slowly to the Dead March from “Saul” to the ground consecrated by the Archbishop of York and formed up in a great triangle, Admirals and their staffs in the centre. There must have been 3 or 4 thousand officers and men there”.

Whilst the British lost many more men and ships than the Germans, the battle was a victory in the sense that Admiral Jellicoe had forced the German navy back to its port where it remained for the rest of war, enabling a debilitating blockade of Germany.

Like thousands of other families, Alex’s great grandparents were left with only memories of their son. For Kathleen, she had a photograph developed that was taken on the boys’ last day together just before they sailed out of Rosyth.

Bertie wrote to his mother,

“I am so glad we had it taken, and we will value it more than any other, for it was taken less than 10 minutes before we said goodbye to Archie for the last time. I don’t know if you saw him again…but I never did… I do so sympathize with you carrying on your job in a house where every chair must bring back the dearest memories of Archie”.

Bertie served in the Navy for another 40 years until his retirement as a Rear Admiral. His mother grieved every 31st May at home in Edinburgh, inviting family friends to a shrine of flowers around a photograph of his midshipman son, a long way from the dark wastes of the North Sea where her son was lost.

(Courtesy of Alexander Kasterine)

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Benbow community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2871

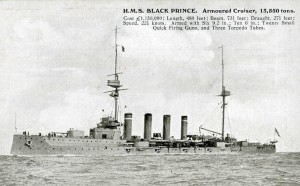

HMS BLACK PRINCE

The deadly loss of an entire ship’s company at night.

During the deployment, Rear Admiral Sir Robert Aubuthnot, ran dangerously close to Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty’s flagship. In fact, of his four ships, only two managed to cut across – HMS Defence and HMS Warrior. The Duke of Edinburgh and HMS Black Prince got left behind. Searching for her sister ships in the night, Black Prince, stumbled on the entire German battle line and was blown to pieces.

HMS Black Prince

I’ve been over her wreck on the North Sea in April 2015 and seen the extended hull torpedo launch ramp. She went down fighting. 857 officers and men to their graves.

Kenneth King’s grandmother’s brother, Jack Butlin, died on HMS Black Prince. when she mistakenly thought that the line of ships she had found in the night were “friendlies”. The German line was between 750 – 1,200 yards distant. At that distance they did not have a chance although they had managed a turn away and were launching torpedoes at their aggressors. Dr. Innes McCartney was able to work out the ship’s direction of turn.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Black Prince community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2773

HMS BLANCHE

Rhys Roberts’ grandfather, Samuel Robert Vaughan Roberts, was at the Battle of Jutland as a stoker aboard HMS Blanche under the command of Reginald Drax, later Admiral. He joined the Royal Navy when he was 18 in November 1913 for a twenty-two year contract.

HMS Blanche, Roberts is in the center of the first row.

When he finished in 1935 he thought he had retired but was called for duty again in 1939, and finished duty with the RN in 1947. During both World Wars and the inter war years he was involved in many operations on many different ships including HMS’s Valiant and London. He worked his way up through the ranks to Chief Petty Officer and Chief Stoker. He died in 1973.

(Courtesy of his grandson, Rhys Roberts)

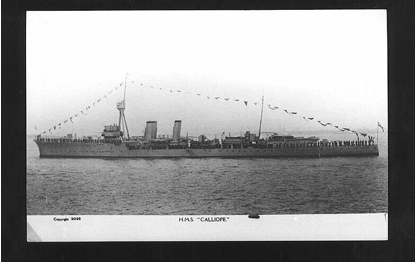

HMS CALLIOPE

HMS Calliope was the flagship of the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron and directly attached to the Grand Fleet. In command was Charles E. leMesurier, John LeMesurier’s father.

Calliope was to be very heavily engaged in fighting back the German torpedo attack that led to Jellicoe’s Turn Away. She was hit three times and around a dozen men killed. Many years after the battle (actually in 1932), Jellicoe later wrote that he should have used the 4th LCS more effectively, particularly in the scouting actions when contact had been lost.

Sir James Spooner’s father had been at Jutland on the Calliope as a Lieutenant. He was later awarded a DSO in 1919 and promoted to Captain. . He had gone to Wilhemshaven and had heard about the extensive damage that had been suffered by the German ships.

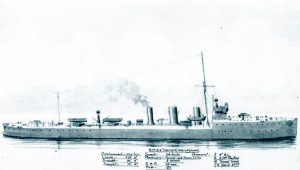

HMS Calliope, flagship of the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron at Jutland

Later, in 1920-21, he was chosen as the Navigating officer on HMS New Zealand when Sir John Jellicoe later made his Dominion Tour. He’d been a great fan of the Admiral.

HMS New Zealand in the Panama Canal. Part of the Dominion voyage 1919. In Gaillard Cut (Kindly submitted by Sir James Spooner who had been a friend of my father, George).

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Calliope community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2568

HMS CANADA

Like Agincourt, build originally for the Turkish Navy, HMS Canada was built for the Chilean navy. The 28,600 ton battleship was based on the Iron Duke design but carried heavier guns (14inch) and had an extra three foot beam. Unlike the Turks, the Chileans actually wanted to sell one of their ships and accordingly HMS Canada was brought back and completed her refit in September 1915.

HMS Canada

Initially she was part of the 4th Battle Squadron and later, after Jutland, transferred to the 1st Battle Squadron.

HMS Canada at Jutland during the deployment. She is astern of HMS Superb.

After the war she was sold back to Chile and became the Almirante Latore.

The Dowager Countess Jellicoe on a visit, I believe, to the Almirante Latore (date unknown, private collection).

She is wearing a pin depicting HMS Iron Duke.

HMS Canada has been lovingly restored by the Friends of the Royal Navy and will be part of the NMRN Jutland Exhibition in May 2016.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Canada community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2968

HMS CAROLINE

Caroline nearly gave the British another 15 minutes of daylight gunnery

HMS Caroline holds a special place in the hearts of all those connected with the Battle of Jutland. She is the last survivor and has been lovingly restored with monies from the Heritage Lottery Fund. I was fortunate enough to visit her before the rennovations startedy.

Nick Jellicoe visiting HMS Caroline in 2013 shortly before

her rennovation.

Built in Birkenhead in the Merseyside, the 446 foot light cruiser, weighting 3,750 tons, was launched in December 1914. She was a beautiful sleek sight.

After Jutland Caroline served as a drill ship till 2011 though she had a short spell during World War II serving as an operational headquarters for the management of the transatlantic convoys.

The following is an account of her role at Jutland told by Warrant Officer Frederick Fielder.

« The ship left port on Tuesday 30th May in company with the remainder of the Grand Battle Fleet. A quiet night was passed as regards the Fleet, but it proved to be a somewhat exciting one aboard, owing to a slight steering gear defect which necessitated the hand steering gear being connected, the ship being steered by it for a couple of hours. The following morning we were informed by our Captain (Captain R. Ralph Crooke), with the aid of a sketch map, of the duties of our squadron in connection with the forthcoming fleet movements. This showed that we were to be the most advanced squadron in the movement which, it was hoped, would draw the German fleet from the Kiel canal where it had reposed in security for so many months.

Warrant Officer Frederick

Fielder, HMS Caroline

Our position was to have been north of Zealand Island. Here we hoped to see something of the German ships, having wished to do so for a year and a half without having the good fortune to sight them, although we came within distance of them when the Blücher was sunk. We were told however to form an escort for the Lion, which was damaged in that engagement, but later returned safely to port.

During the forenoon, we were informed that the Battle Cruisers were in touch with the enemy. Later we were told that their Battle Fleet was out, but a long way off. Our direction had already been altered to bring us up with the Battle Cruisers. We had been to action stations and made all preparations for battle should we have the good luck to get on the scene of the engagement before the enemy scattered for port, as was their usual custom when meeting any of our ships.

At ten minutes past three, the alarm rattlers were sounded, and everyone at once rushed off to their stations. We had the exciting news that we were nearing the scene of conflict, and soon we could hear the sound of gunfire. Shortly afterwards coming in sight of our Battle Cruisers who were firing broadside after broadside. We rapidly closed on them, taking up positions to protect them from torpedo and submarine attacks, being for some time in company with the Lion, the flagship of the battle cruiser squadron flying the flag of Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty, At this time the whole of our fleet was in a very close formation, lines of battleships intermingled with lines of cruisers, light cruisers and destroyers. These ships, to the eye of an observer unused to naval tactics, would have appeared a hopeless mess of ships of all classes and sizes, even to us in the Grand Fleet who had regularly been engaged in similar practice evolutions at sea during the whole period of the war (now of nearly two years duration) it seemed a somewhat confusing situation as our particular squadron, (4th Light Cruiser Squadron) although in correct positions line abreast, had such a restricted area to manoeuvre in, owing to being between our own big ships, that the men manning our port guns, were talking to the men manning the starboard guns of the next ship to us, so close were we to each other, these men were chaffing each other about a boat race, which had taken place between the two ships the previous Saturday and while engaged in this pleasant pastime, big shells were falling round the ships, dropping perilously near, one destroyer just astern having a funnel knocked over the side, and another having her bows crumpled up, which necessitated her dropping out of the line, the men mentioned above still delighting each other by their wittiness.

The nearest big ship to us at the time, the Lion, had a shell inboard under the forecastle, causing a fire which must have given them trouble, as volumes of smoke were issuing from her port side, on several occasions belching forth with renewed intensity. However she was able to continue her course and firing.

The fleet had now spread out over a larger area, assuming a different formation, we being single line ahead by the side of the battle cruisers, who were pounding away at the enemy, now quite visible to the naked eye, their shells falling around us, at times being uncomfortably close, it being nothing short of marvellous that we were not struck, although in the light of a later experience, our numerous escapes were not so close as they might have been.

As our guns were of no avail against the big ships of the enemy who were only within range of the big guns of the battle ships and battle cruisers “Carry on smoking” was piped and we were in the position of being spectators of the fight now raging with intensity. Some difficulty had been experienced in keeping our men, who were engaged in ammunition supply and other multifarious duties below at the stations as they had now been some hours standing by doing nothing and naturally wanted to see the ‘scrap’. When the word was passed to ‘Carry on Smoking,’ they scrambled up on deck keeping handy to hatchways, ready to jump down to their stations should the necessity arise.

It was a glorious sight to see our big ships firing their broadsides. On two occasions, when their shells had found their billets on an enemy ship, which would be observed by the shells bursting against their sides loud cheers were given by our men, who also clapped as if witnessing a football match, being quite unconcerned about the big shells that only too frequently passed over our heads or dropped in the water near the ship.

About this time, a large ship was observed on the far side of our battle cruisers to have burst into a vivid sheet of flame and when then the smoke cleared away, she was seen to be in two portions, as her stern was showing a few feet out of the water, while her bow was some forty or fifty feet standing perpendicularly out of the sea. We feared that it was one of our own ships, and after events proved that it was the Invincible.

The firing was now going on with increased intensity, and this ship in particular was extremely fortunate in avoiding not only shells but torpedoes, for two were observed to be coming towards the ship, but by splendid handling of the helm, one passed on each side of the ship and on another occasion, one was making for us, but fortunate, it was nearing the end of its run and was traveling at only about six knots and as it neared the ship, the wash of our propellers turned it away just sufficient to clear the stern by inches.

Dusk was now coming on, and the light, which had been very bad for firing all day was failing, and the German ships were getting very indistinct and were apparently getting very badly mauled by our shellfire.

A periscope was then observed some way off and in line with our course. Soon afterwards a bump was felt along our bottom. A man coming up from the fore boiler room reported that a distinct shock was felt there under the bottom. Whether we touched the submarine and sank her is not known, only that something was evidently struck.

A destroyer attack was now made on our battle fleet, and our squadron was detached off to repel it which was done with complete success, at least two of the destroyers being sunk and our leading ships ran in very close to the German Fleet, firing torpedoes and getting rather badly knocked about by the big guns of the enemy. However, all returned safely, our Commodore ship with nine killed and several injured.

The enemy, who were now getting punished unmercifully by our big ships, suddenly set up a smoke screen, and turned away under cover of it, evidently trying to get back to their harbour. They eluded us for the time being, and after a while, one half of the Officers and Men went below to get a meal as we had been some hours without an opportunity of getting one. A short time afterwards our alarm rattlers sounded off, and on dashing to our stations, we found that we were steaming on an almost parallel course to a line of German battle ships or battle cruiser being quite close to them. I had just come up on deck and on observing them said “Why, they are German ships” which could be easily seen by their distinctive funnels. Our starboard torpedo tubes were trained on them, and as we fired two torpedoes, so the nearest ship to us opened fire with a broadside of eleven inch guns, but we were lucky enough not to be struck, although it was a straddle, ie some shots falling short, others going over and by all the rules of gunnery, the next broadside should have finished our career, especially as we were at such close range and the enemy set up a large star shell to light us up, but our Guardian Angel was still protecting us, for the next broadside missed us, going over the shells screaming over our heads, some dropping between us and our own ships on he other side. By this time, we had set up a smoke screen and escaped from an extremely perilous position, for this small ship would have been literally blown off the water had any of the broadsides fired at us got home. However, we did escape, due no doubt to the erratic German shooting, their men probably being in a state of panic or blue funk as they must have received fearful punishment from our hands No more was seen of them that night by the main fleet, and we cruised about for the few hours of darkness, no one turning in as all hammocks and Officers bedding was stowed away in case of fire. We fully expected, and fervently hoped that we could finish the battle the next day and have another glorious first of June to add to the assets of the British Navy.

Darkness, such as it was, had now set in and we had time to finish our interrupted meal, which consisted of cold meat and bread, as there had been no opportunity of cooking anything. The other watch was more than relieved that the guns had stopped, and we settled down to our ordinary night war routine at sea.

All hands were roused to their stations at two a.m. And we fully expected to come in contact with the enemy again, as from ten O’clock to midnight, heavy firing had been taking place away off our port quarter, the light from the guns being reflected in the sky. I was on watch as Searchlight Control Officer, and being stationed aft had a full view of the reflections, which were sporadic, but very vivid at times. It afterwards transpired that our Destroyer flotillas were making a night attack on the enemy fleet, which was endeavouring to get back to harbour. They had evidently had quite enough for the day. We however, were only too anxious to continue the fight, and would have given much for four more hours of daylight.

The fleet cruised about in the vicinity of the scene of action all the following day. Scouts were out in the hope of seeing the German fleet again, or even any lame ducks. There was no German fleet in being though, and it cannot be too much emphasised how disappointed every man in our fleet was when we had to give up searching for them and return to our base to replenish with coal, oil and ammunition, without having the opportunity of finishing the battle.

Nothing of importance happened during the 300 or 400 mile trip back, except that the sea, which had hitherto been calm, was rising, and fears were entertained concerning the safety of the (name not given), one of our big Battleships, which had been torpedoed, but was making her way into harbour ».

The ship in question was the SMS Westfalen. Caroline’s torpedo had run absolutely true and went straight under her.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Caroline community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2741

Chief gunner James Weddick :

http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/horror-epic-sea-battle-world-7868609

HMS CHESTER

Who was the man who saved Captain Lawson?

William Roy died at the battle of Jutland aboard HMS Chester. He was the Chief Yeoman of signals and reputedly saved the life of Captain Lawson as they came under fire from Admiral Boedicker’s light cruiser squadron. Roy’s grandson has two questions:

· Are there any living relations of Captain Lawson who might be able to put some light on this event?

· What medals were awarded to the crew of the Chester?

HMS Chester and HMS Canterbury were out of each wing of Horace Hood’s 3rd Battle cruiser Squadron’s flagship, HMS Invincible. With her were also from the 4th destroyer flotilla: HMS Shark, HMS Acasta, HMS Christopher and HMS Ophelia.

HMS Chester. She’d been commissioned less than a month.

Captain Robert Lawson heard the sounds of Hipper’s battle cruisers and headed in that direction. Unluckily he headed straight into the SMS Frankfurt, of Hipper’s 1st Scouting Group, steaming five miles north-west of the disengaged side of Hipper’s battle-cruisers, with the Wiesbaden, the Pillau and the Elbing. They had been busy chasing Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron and the surviving four battle cruisers of Beatty’s two battle-cruiser fleet squadrons, the 1st and the 2nd.

Chester signalled a challenge and made an error on the response. She approached to within 5,000 yards. As a newly commissioned ship, her crew was not completely battle-ready and unprepared for the withering fire that was let looses. Within three minutes most of her ten guns had been hit and three were out of action; the forward one was the first to go. That was where Jack Cornwell was manning a gun.

The small and very intimate memorial to HMS Chester and her crew in Chester Cathedral.

Below decks there were men lining the passageways with horrific injuries to their legs and feet. The shrapnel has scythed most men’s limbs off.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Chester community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2303

HMS DEFENCE

Why did Arbuthnot charge the German line?

HMS Defence, the flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot was one of the terrible casualties of Jutland. Arbuthnot had seen the engagement between with Wiesbaden and some of Horace Hood’s ships. Some say he wanted to intervene and prevent the Wiesbaden escaping, others that he was deploying his squadron to take it round to the back of the line. He still passed dangerously close to Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty’s flagship missing her by around 200 yards. Of his four ships, only two managed to cut across – his own, HMS Defence, and HMS Warrior. The Duke of Edinburgh and HMS Black Prince didn’t.

The two ran into a hail of fire and Defence was seen to explode in front of the passing ships of the Grand Fleet. Warrior got away.

Arbuthnot was taking his ships to the rear of the line to take up a new position rear of the dreadnoughts. He should have passed behind the Grand Fleet. Instead, he passed in front, not only obscuring British fire but also, because he attacked the Wiesbaden, attracting fire from a number of powerful German ships. Jellicoe had wanted to remove him from command a few years earlier but had been refused by the admiralty. Arbuthnot was disliked by his men for excessive discipline.

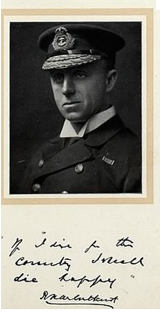

Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot’s prophetic words.

She was an old armoured cruiser and as such should probably never have been part of the British battle line. She wasn’t built for such a role. Rather her role was conceived of as being an armed ship that could interdict an adversary’s merchant shipping at sea.

The stern of HMS Defence (Public Domain)

One of the terrible flaws in the design of Defence was the midships between the main fore and aft 9.2inch Mk XI guns. Here were ten secondary guns, all BL 7.5 inch Mk V, five on each wing, supplied with shell and cordite from the main magazines where strict magazine handling practices were probably upheld but where, beside each gun, great bins, capable of holding between 40-60 cordite bags, were built.

An embroidered memory of HMS Defence (courtesy of the National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth)

In April 2015, on the North Sea Expedition organized by Gert Normann Andersen of the new Sea War Museum in Thyborøn, Denmark, Dr. Innes McCartney and I were allowed a privileged view of her wreck using the powerful multi beam sonar scans of the M/S Vina, one of the pipe-laying ships from Andersen’s JD-Contractor A/S company fleet. McCartney has spent more than fifteen years diving the wrecks of Jutland and wrote about the archeology of the Defence. My memory of the day is very different from what his would have been. Arbuthnot had been ashore two days before Jutland and had been playing tennis with my grandmother, Gwen Jellicoe, the Admiral’s wife.

A small village link between Jellicoe and a Royal Marine on HMS Defence.

George Henry Buckle was a Royal marine artillery Bombardier on HMS Defence. He came from a small village between Eton and Windsor called Clewer, where he met his wife. She had been born and bred in Pennington near Lymington on the edge of the new forest in Hampshire. They met when Andrew Wright’s great grandmother was employed by the local vicar as a house keeper, a job she applied for whilst living in Pennington. They married and lived in Southsea Portsmouth, next to Eastney barracks at 80 Cromwell Road, Andrew is still researching in which turret his great grandfather was in when he died. The link is that one of John Jellicoe’s ancestors had lived in Clewar. In what was then the manor house. More work to be done on this!

(courtesy of Andrew Wright)

SOME MORE STORIES :

Dr. Innes McCartney. The Armoured Cruiser Defence: A Case Study in assessing the Royal Navy shipwrecks and the Battle of Jutland, 1916, as an archeological resource.

Go to “Source Materials”

The Liddle Archive, Leeds University

Imperial War Museum HMS Defence community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/381

HMS ENGADINE

The only seaplane carrier at Jutland

The Engadine was originally a channel ferry. She became a Royal Navy ship in 1914 and a large hangar was constructed behind her funnels and a crane added to handle the lowering and boarding of her four Short 184 seaplanes. Turrets were not yet used for take-offs and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) had not yet experimented with flight deck take offs or landings.

Seaplane carrier HMS Engadine

At Jutland, Lieutenant Frederick S. Rutland with Assistant Paymaster G.S. Trewin, following Beatty’s orders took off to reconnoitre the German battle cruiser fleet. They saw Hipper’s turn southward but were eventally brought down when a fuel line was damaged. None of her radioed signals got further than her mother ship, the Engadine.

Lieutenant Frederick S. Rutland and his Short 184

Lieutenant Frederick S. Rutland (Private Collection. On the left)

Returning to port, the Engadinetried to tow the damaged HMS Warrior and was able to take her crew off. Rutland exhibited a second act of courage when he dived in between the two ships to rescue a wounded sailor who had fallen in and was in danger of getting crushed. He was decorated for his bravery.

SMS DERFFLINGER

Some special conversations with Georg von der Hase’s grandson

Georg von Hase was the Gunnery officer on SMS Derfflinger. She was the second ship in Hipper’s line of battle when fire was opened _at 15:48 from the Lützow. Von Hase wrote about his experience at Jutland in « From Kiel to Jutland » and it has become one of the classics to which naval historians turn for a glimpse of what it was like on German ships.

I met with Dieter Ammer, von Hase’s grandson, at his office recently when I was in Hamburg. We could have talked for hours but one of the things that I came away with were some images of what his grandfather looked like. I’d never seen any images before despite him having been a prolific writer.

Sadly, his grandfather in 1968 had given him the ship’s official logs to carry out of East Germany and keep with him in safety in the west. They never made it. The young, eighteen year old was arrested at the border between East and West Germany. The book was confiscated and then stolen by the border guards. He himself was locked up with no idea what his fate would be for days, without being able to inform anybody. Eventually he got out but was never able to retrieve the records that his grandfather had passed on. Maybe one day we’ll see them.

HMS GALATEA

A friendship that has lasted through generations

The opening shots of the battle of Jutland were fired at 14 :28 by the light cruiser, HMS Galatea, out on the easterly wing of Sir David Beatty’s Battle-cruiser Fleet. She was part of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron with her sister ship, HMS Phaeton.

On board was the father of my own father’s best boyhood friend, Tim Marten. I know Tim’s daughter, Jenny Ingham Clark, and her brother, Michael, wrote about Tim’s life and his memories of my own father, George (Lorna Almond. A British Achilles.The life of George, Earl Jellicoe)

One such occasion was when George had his friend to stay with him over the holidays at their Isle of White house, St Lawrence Court just abover Ventnor. George persuaded Tim to go peach picking in the garden even though he’d been expressly forbidden from doing so. The peaches were being allowed one final day of ripening on the trees before being served at tea for some special guests. Neither King George V nor his wife Queen Mary enjoyed the fruits of the Admiral’s garden.

Frank Marten ([Francis Arthur Marten, 1879 – 1950), Tim’s father, described the some of the highlights of the day. One was the meeting of the two British fleets – the battle cruiser Fleet and Grand Fleet and the incredible complexity of the deployment at « windy corner ». He also told the story of the chance meeting with the German Fleet. The Galatea had been late receiving the signal to turn north and rejoin the main body of Beatty’s fleet as he steamed northwards to make the rendezvous point with Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet.This meant that she continued on her easterly track and eventually saw the smoke from the stationary N J Fjord. The Germans saw the same smoke and the Elbing sent two destroyers in to have a closer look. The B.110 and B.109 sped off and while one stood off, the other sent a boarding party. The Germans were seen by the Galatea which signalled Beatty and then at 14,000 yards, her maximum range, opened fire.

Tim Marten (L) and my father, George, with my elder brother in his arms (Private Collection. On the left)

Tim Marten and my father remained friends till my father’s death in 2007. Tim passed away a few years later.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Galatea community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/3016

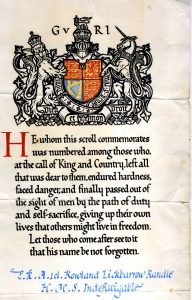

HMS INDEFATIGABLE

The fates would not give him a second chance

On 28th October 1914, at the time Turkey entered the 1st World War my grandfather, Rowland Lickbarrow Randle, a Royal Navy petty officer, was ‘serving the pinnace’ at the British Embassy in Constantinople (now Istanbul). He and another petty officer were required to stay behind and destroy anything in the embassy that might be of use to the enemy and then make their way back to England in borrowed civilian clothes. To enable their escape they were given a special passport to give them safe conduct through Bulgaria where they were to get on any available merchant ship they could find bound for England.

Had it been known they were in the British Navy they would have been killed or imprisoned. They managed to get on a ship and in mid ocean a passing British war ship was stopped from which one of the crew identified Rowland and he and his colleague were transferred to the war ship and returned to England.

Rowland Lickbarrow

Fate was not kind though as on return he was posted to the HMS Indefatigable which was the first ship to go down at the Battle of Jutland. Had the merchant ship he had found passage on not been intercepted and he had arrived back in England a little later then he would probably have been posted to a different ship.

(Coutesy Malcolm Randall)

HMS IRON DUKE

My grandfather’s flagship. Not the usual stories

The story of HMS Iron Duke became so embedded in our family history that there are reminders in many of our family photo albums of the other lives of the Duke. One was my grandfather’s love of sailing. Seen here in New Zealand when he was serving as Governor-General.

The Admiral at sea with another Iron Duke.

There’s a lovely story in one of Vladimir Nabakov’s books (Speak, Memory) when he talks about his own father :

“There, with a certain old-world naiveté, my father had mentioned making a present of his Swan fountain pen to Admiral Jellicoe who at table had borrowed it to autograph a menu card and had praised its fluent and suave nib. This unfortunate disclosure of the pen’s make was promptly echoed in the London papers by a Mabie, Todd and Co;, Ltd, advertisement, which quoted a translation of the passage and depicted my father handing the firm’s product to the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet, Under the chaotic sky of a sea battle.”

Here’s a copy of the advertisement (excuse my rather bad photo) that resulted :

Admiral Jellicoe’s advertising for Swan fountain pens (Courtesy of Nissim Marshall who kindly brought the Nabakov connection to me)

Only discovered this year in our attic, a more informal photo of the Admiral and the Iron Duke.

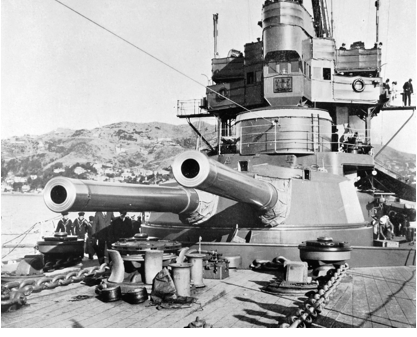

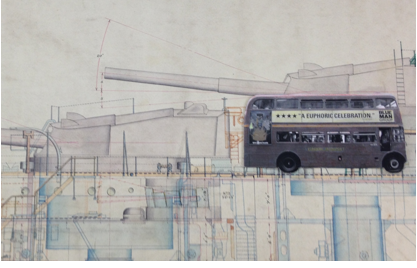

An idea of the size of her guns can also be better illustrated by comparing the size of a London red double decker and her forward 13.5inch guns. Andrew Choong at the National Maritime Museum’s brass foundry holds all the ships’ plans and likes to use this illustration to get the point across to visitors.

What a London double decker bus would have looked like if placed beside one of Iron Duke’s 13.5inch guns.

The ties between the Iron Duke and the families continue today with regular visits to and correspondence with to-day’s Type 23.

The Latham family visiting HMS Iron Duke on an Open Day in 2015. From Left to right: George Latham (Richard’s second son), Richard Latham (my cousin), Elliot Latham (George’s son) and myself.

Ron Horabin. A gentleman – literally – and an inspiration

Still the fondest memory I have is of the day when Ron Horabin, an ex-brickie from Runcorn, Liverpool, astonished me with the generous gift of the scratch model of the Iron Duke to the Jellicoe family’s safekeeping and use during the Jutland Commemoration. He’d taken three years to build her. It was an extraordinarily powerful moment for me and I often thought of what Ron would have thought if he could have seen his model in Denmark and Germany’s best maritime museums. R.I.P Ron., thank you.

A proud day for each of us. Ron Horbain and Nick Jellicoe.

Today’s Iron Duke back at Jutland Bank one hundred years later

On May 31st, the Iron Duke was well remembered on the North Sea at Jutland. She accompanied HMS Duncan and the German frigate Brandenberg at the wreath laying. On HMS Duncan, Iron Duke‘s battle ensign and her Jack both flew for the first time in a hundred years. Both had been at Jutland.

Batle of Jutland Commemerations

HMS Duncan joined FGS Brandenburg and HMS Iron Duke to commemorate 100 years since the battle of Jutland.

An interesting picture of the kind of man Jellicoe was

I recently received an e-mail from someone whose grandfather was a young telegraphist serving in HMS Iron Duke. Shortly before battle was joined, Admiral Jellicoe asked him to make two mugs of chai and report back. “My Grandfather did so and offered the Admiral one mug before asking who the second was for. Jellicoe replied that the second mug was for him and as they drank their chai, took the time to talk to my Grandfather about what to expect during the battle, and to encourage and reassure him. I clearly remember my Grandfather telling me the story more than 60 years after the event and it obviously had an extremely positive impact on him – indeed he used it to illustrate how an officer should always find time to look after his subordinates”. I was very touched by his story.

(courtesy of Richard Cole-Mackintosh)

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Iron Duke community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2915

HMS INVINCIBLE

At the very moment Invincible’s shooting is at her best, she falls victim to another magazine explosion.

Invincble went to the rescue of the Chester, one of her scout cruisers, which had been chased by four enemy cruisers (the Frankfurt, Pillau, Elbing and Wiesbaden) and had taken heavy casualties. At 17:53 Invincible’s 12-inch guns opened fire at 8,000 yards. The Wiesbaden, last ship in the line, was hit as she turned to run: one of the Invincible’s massive shells had burst through the side in the engine room bringing her to a stop.

A half hour later Invincible had – after having steering problems – joined up with Beatty’s line and roughly 9,000 yards distance from Hipper’s battle-cruisers. At 18:26 she was heavily engagd with the Lützow and causing heavy damage so much so that Rear Admiral Horace Hood encouraged his gunner officer, Herbert Danreuther (a godson of Richard Wagner) saying “Your firing is very good. Keep at it as quickly as you can. Every shot is telling”.

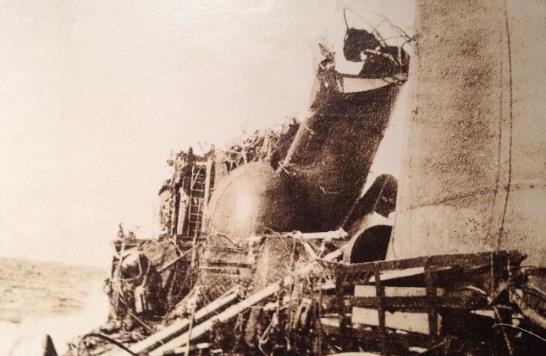

Minutes later, the fog back that had been protecting parted and the ship was lit up by the sunlight which fell trough. At 18:31 Lützow now landed a shell that penetrated Q turret and set her magazines on fire. The explosion was like a small nuclear mushroom cloud.

HMS Invincible seen astern of one of her sister ships at Jutland.

Passing ships were confused. They had not seen what had happened and at first cheered, thinking it was a German ship.

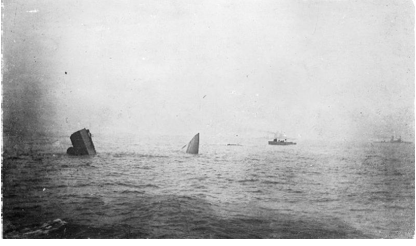

HMS Invincible broken into two parts, bow and stern, with the destroyer HMS Badger picking up survivors.

There were 6 survivors. Four were picked up by Badger. Two, including Hubert Danreuther, were seen at 19:02 by HMS Colossus. At 19:05 Jellicoe himself signaled Badger: “Is wreck one of our ships? Reply – Yes, Invincible”

Rear Admiral The. Hon. Horace Hood, 3rd Battle

Squadron flew his flag from HMS Invincible.

When the surviving ships came back to Rosyth, Hood’s family were gathered and eagerly awaiting the father of the family. They had not heard the news. It must have been crushing.

Lady Hood wrote a number of letters to re-assure those with husbands who had not returned of their last moments. One such letter concerned Charles Overy in a letter to the Dorking and Leatherhead Advertiser, on January 27th 1917.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10209608712800891&set=o.250273295322684&type=3&theater

Two friends lose brothers the same day. On the same ship

Below is a letter from Oldric Portal, whose younger brother, Raymond, died on Invincible. It is written to his friend Tom Fisher who also lost his brother – Charles – on Invincible.

Oldric’s letter summarises the report that Hubert Dannreuther, the Gunnery Commander on Invincible, presented to the Admiralty and the King. Dannreuther was one of the six who survived, having been up on the mast turrets, observing the fire and taking ranges

Report from Oldric , HMS Invincible, giving a clear summary of the sequence of events before Invincible exploded (Kindly submitted by Deborah Curle, the great-niece of Charles Fisher, seen below, was serving on HMS Invincible.).

Charles Fisher, HMS Invincible. His sister, Adeline, was Vaughan Williams’ first wife, who apparently never recovered from his loss. It gives the Jutland Concert which took place on June 15th 2016 at the Barbican Center, some closer connections with the battle than one might at first imagine.

The telegram that went to inform next of kin of a death in action was Curt beyond belief.

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Invincible community:

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2591